Many parents feel frustration when their children come home using arithmetic methods and tools different from what they learned. “Why can’t they just [add/subtract/multiply]?” is a common refrain for caregivers of children in middle elementary. Then, finally, the children are taught the same method the parents know, but… the language has changed! In math, carrying and borrowing are both now called regrouping. Why, oh why, can’t they just teach it the same way with the same words?

Regrouping is a general term that includes both carrying and borrowing. This change of language more accurately describes the math structure, keeps vocabulary consistent all the way through math education, and agrees with how we use the words in standard English.

We can think of almost any whole number as a “part + part = whole.” Regrouping in math can mean either looking at the whole instead of the parts, or changing up the parts that make up the same whole. Look at the colors of the boxes in the image. Here we can see visually different ways of grouping 6 into its parts: for the cherry red boxes, we see that $5+1=6$. The yellow boxes show us that $4+2=6$. The purply-blue boxes show us that $3+3=6$, the deep red $2+4=6$, and finally the green $1+5=6$.

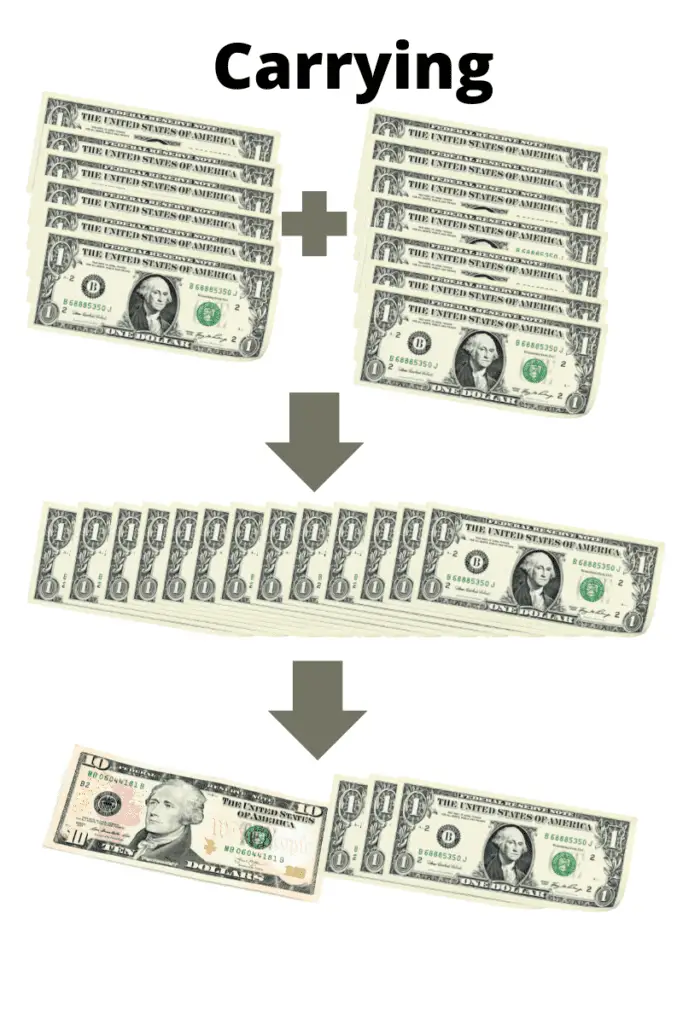

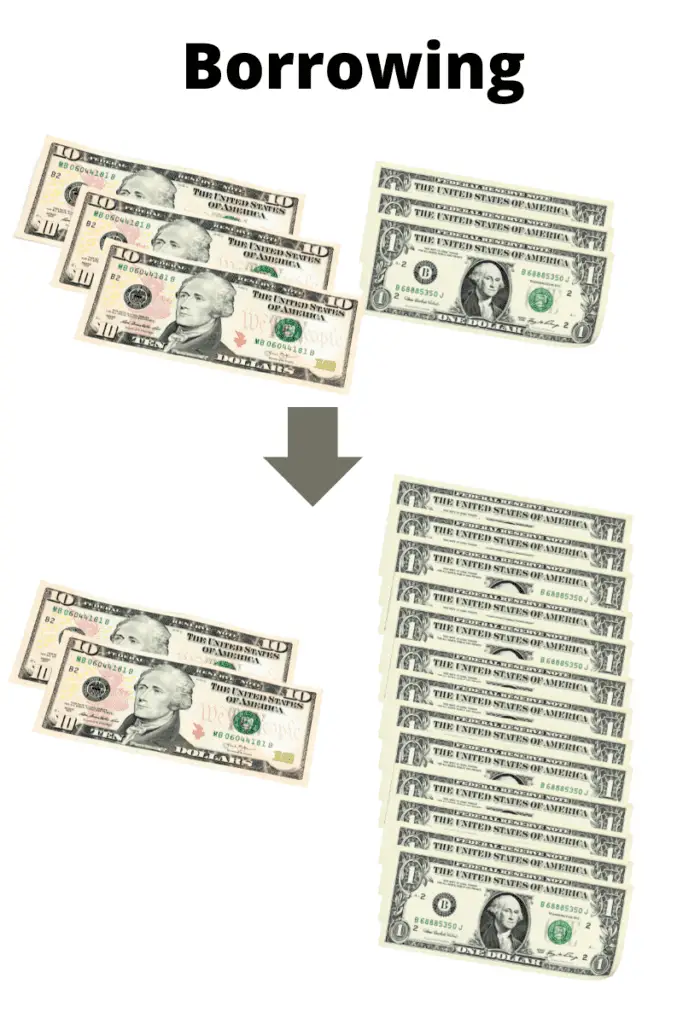

This is a lot like making change: you might want to turn a \$10 bill into ten \$1 bills, or you might want to turn five \$1 bills into a \$5 bill. In adding multi-digit numbers, we sometimes turn ten 1’s into one 10 (or ten 10’s into one 100, etc.) We used to call this carrying. In subtracting numbers, we sometimes turn one 10 into ten 1’s (or one 100 into ten 10’s, etc.) We used to call this borrowing. Regrouping refers to choosing a different grouping, a different set of “parts”, for the same whole total amount.

This post was originally published on mathteacherbarbie.com. If you are viewing this elsewhere, you are viewing a stolen copy.

But why did the language change? Read on to learn more.

More accurately describes what’s going on

When we “carried the one,” we actually took ten of the place value we just added and turned it into one of the next place value (e.g., we added 7+6 to get 13, which we then split up (regrouped) into 10+3, writing the 3 and carrying the 1.) We regrouped by changing up the grouping of the same amount, by re-combining some of the parts. When we “borrowed,” we actually took one of the next place value and turned it into ten of the current place value (e.g., we took one away from the top of the tens column and turned it into an extra ten 1s instead.) We regrouped by changing up the group of the same total amount, by breaking it into parts.

Consistency within Math of similar language for similar actions

Where else in math have we ever used the words “borrow” or “carry.” Regrouping, however, will come back into play when students learn about multiplication, fractions, decimals, and even algebra. As just a few examples:

- When your child learns about factoring, we can use the same grouping language: the 30 boxes of tea in the drawers, shown again below, might be grouped as:

- one group of 30 (factors: 1 and 30) — all the boxes below together

- two groups of 15 (factors: 2 and 15) — two drawers with 15 boxes each

- three groups of 10 (factors: 3 and 10) — three rows (going across drawers) with 10 boxes in each row

- five groups of 6 (factors: 5 and 6) — five types of tea with 6 boxes of each type

- six groups of 5 (another view of factors 5 and 6) — imagine making gift boxes with one box of each type in it; you’d end up with 6 gift boxes

- ten groups of 3 (another view of factors 3 and 10) — ten columns (going “down” drawers) with 3 boxes in each column

- fifteen groups of 2 (another view of factors 2 and 15) — if these employees go through two boxes a week, this collection would last 15 weeks

- thirty groups of 1 (another view of factors 1 and 30) — 30 individual boxes of tea

- Fractions can be thought of as regrouping a single whole into smaller parts, eg 5 parts (called fifths) or 7 parts (called sevenths).

- In decimals, regrouping will come up as a combination of the regrouping ideas from addition/subtraction and fractions.

- In algebra, your student will revisit the idea of factoring, this time with more “generic” and less specific numbers, known as polynomials. You may even have learned a strategy of “factoring by grouping” in algebra. As it turns out, this use of the word grouping is closely related to the same grouping terminology your student is learning now.

And these are only a few of the examples of how this term will be used throughout your child’s math education. A consistent language woven throughout allows students to see the connections and more deeply understand how each new skill is related to and expands upon earlier ideas.

Consistency with standard English usage

When we “borrow from the tens place,” do we ever really intend to give it back? What about carrying? We wrote the one up above the other numbers, but did we really carry it there? This type of disconnect between mathematical language and everyday language has contributed to the view that math rules are arbitrary (they’re not) and that they are not connected to things we do every day (they are). These beliefs have challenged math learners for generations, leading to misunderstandings, frustration, and miscommunications all along the way.

If you’d like a visual demonstration of regrouping, check out the video below from the Math Teacher Barbie YouTube channel. For a broader view of grouping and regrouping, check out the post Grouping and Regrouping in Math.

You’ve Got This!