One of the more common definitions of math is the “study of patterns.” To my mind, no tool has proven to be more useful in our PreK-12 study of patterns, as well as numbers, than the array. “Array” is a word frequently used in many fields, including computer science, electricity, finance, and even fashion and art. While it’s often used with a very specific meaning much of the time, in essence each of these instances goes back to the dictionary definition of array as being an ordered or systematic way of displaying or organizing information, items, or instructions.

In math education, we use arrays — and our very human preference for regularity and rhythm — to both bridge and build mathematical principles, relating them to each other, and giving concrete, visual, and often aesthetically pleasing ways of illustrating structures, patterns, and relationships between mathematical ideas.

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase through these links, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. You can read more about how I choose affiliates and products at my affiliate page.

This post was originally published on mathteacherbarbie.com. If you are reading this elsewhere, you are reading a stolen version.

Arrays of Objects: Counting, Units, Addition, and Skip Counting

(The interactive image above illustrates 12 groups of 3, or $12\times 3$. You can move the groups into whatever arrangement you desire — they will still be 12 groups of 3. It was created using the amazing, free tools at polypad.amplify.com.)

In Arrays: Powerful Early Math Tools, I write extensively about how to use arrays in building early foundational math concepts such as counting, correspondence (including one-to-one or pigeonhole principles), adding, communicating units or characteristics, and skip counting (an early precursor to multiplication).

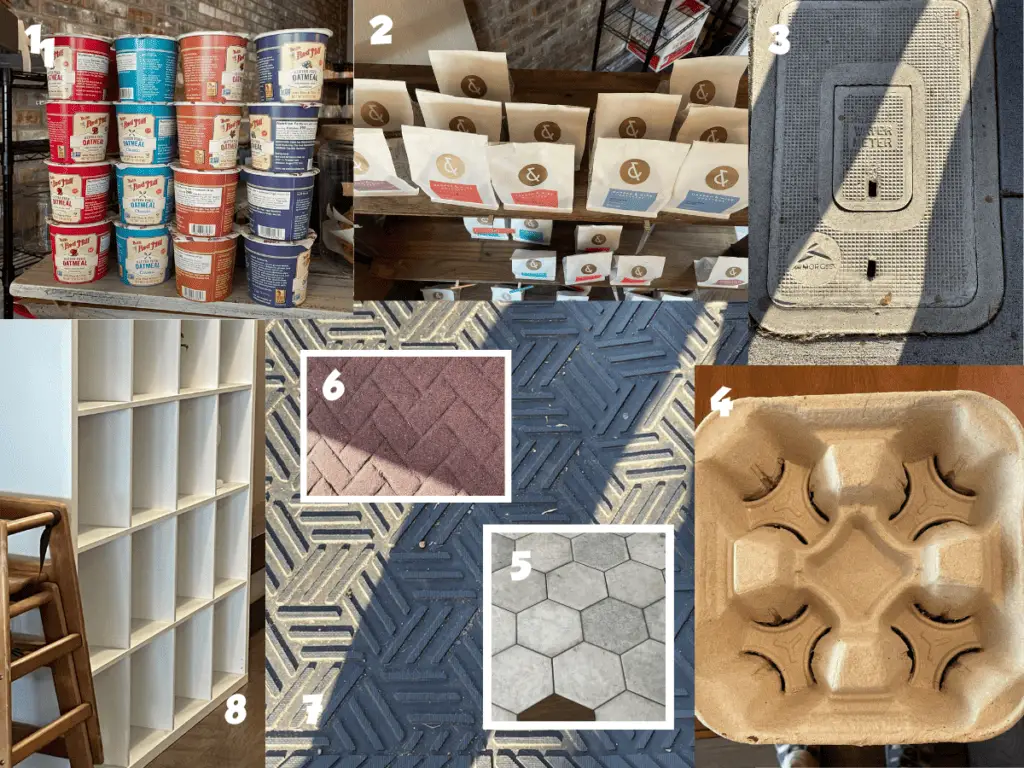

Our human desire for order and organization means arrays surround us throughout our lives. This leaves opportunities for small “math” chats (#talkmathwithyourkids or #tmwyk) between parent and child throughout the day, while enjoying each other’s company. These small chats build number confidence for both child and adult, can incorporate older children or other adults as well, and yield insights about characteristics and patterns each person finds important. The video below, Summer of Arrays, gives one framework to help you engage in and enjoy these small insights and conversations that build both confidence and relationship in positive ways while honoring creativity, artistry, and the early childhood desire for movement and touch.

Rectangular Arrays: Skip Counting, Multiplication, Subtraction, Combining Operations, and Commutative Properties

(The interactive image above illustrates 3 rows of 12, or $12\times 3$. Rotate the array as you desire — it will still represent $12\times 3$ or $3\times 12$. It was created using the amazing, free tools at polypad.amplify.com.)

Not all arrays your child encounters in elementary school will be rectangular in shape, but most will.

*not an affiliate link. Mathforlove.com, contact me! 🙂

Rectangular arrays, as the phrase implies, are arrays in which items are organized in the shape of a rectangle with consistent rows and consistent columns.

Rectangular arrays allow our eyes to immediately recognize inconsistencies, missing components (subtraction!), as well as regularities. The Western world loves to organize its environment into rectangles and right angles, so most of us are surrounded by rectangular arrays from our earliest days. We’ve become used to rectangles as a means of organizing our world.

Because of the easily-spotted regularity, rectangular arrays encourage skip-counting and readily bridge that skip counting to multiplication. In a rectangular array, because “missing” items are easy to spot, it is easy for our brain to trust that each row and/or column is consistent without having to count each one.

Number Tiles: Abstraction (Generalizing Patterns) and Place Value

(The interactive image above uses number times to illustrate both 3 groups of 12 ($3\times 12$) and 12 groups of 3 ($12\times 3$). You can click on these tiles, move them around into rectangular arrays, split apart the 10-groups or combine the singles. Doing this does not change the total number ($36$) in each representation. It was created using the amazing, free tools at polypad.amplify.com.)

It’s not always practical to line up the exact objects we’re talking about in a problem or scenario. This is where abstraction comes in. Abstracting refers to removing or reimagining the context of a problem to more easily examine its patterns and structure. For example, when we learn to count, assigning a number to each item in a group, that count becomes an abstraction representing the whole group, even when the group is not there.

In the classroom, some early tools for learning to think abstractly are counting bears and math cubes (affiliate links). Though the bears are common in classrooms, you could easily use anything you already have a lot of and that your child’s fingers can manipulate — dry beans, paperclips, alphabet blocks, pennies, balls of play-doh, etc. These are great tools for bridging the idea of thinking of counting items in a row (in a line) to different ways of organizing the same items (such as an array!) and learning different counting strategies (such as skip-counting).

On the other hand, math cubes lock together in multiple ways, allowing counted groups to “stick together” and be moved around. Student can make groups of the counted items, move them around, and view them in different configurations. It’s a great tool for learning how to keep track as well as to view numbers and patterns, as well as to create some early abstracted arrays.

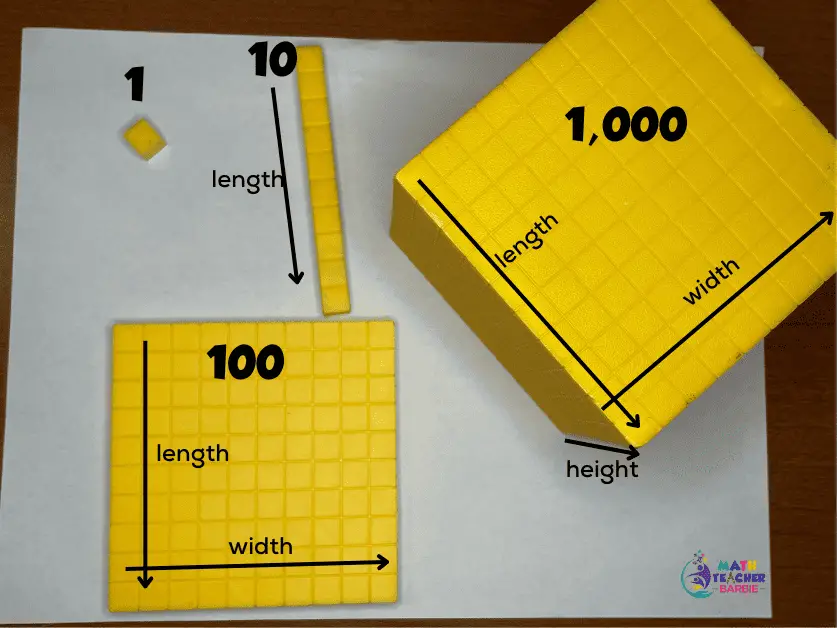

At some point, these early tools will evolve into the classroom use of base-10 blocks or “number tiles” (affiliate link). Base-10 blocks come permanently grouped together into singles (ones), tens, hundreds, and even thousands. One common way these are used, both in person and in print, are to directly represent multi-digit numbers.

Above is an interactive using free, online base-10 blocks from polypad.amplify.com. I’ve set up a first example, and you can examine how the base-10 blocks combine to make the number in purple. When you’re ready to try your own, click on the purple box with the number, choose “Randomize,” and then add and subtract base-10 blocks to represent your new random number.

Base-10 blocks offer subtle number intuitions that serve students well into advanced math.

“Closed” Arrays: Movement toward Symbolism

I love volunteering with math groups at our neighborhood elementary school. Following the interests of one of my second-grade groups who are ready for challenge, we’ve been discussing multiplication. Since they quickly figured out multiplication facts using the numbers 1 through 5, we turned to deepening our understanding of what multiplication is as well as answering one student’s curious questions about squares and square roots.

We observed that most of the multiplication facts we talked about had come in pairs: $2\times 3$ and $3\times 2$ for example. We also observed that a few of the facts weren’t part of a pair, and moreover, these facts all had matching factors: $3\times 3$ and $4\times 4$ for example.

*Not an affiliate link.

So how to deepen understanding, give them a tool they can access for future experimentation and deepening, and even explore square roots? Closed arrays to the rescue!

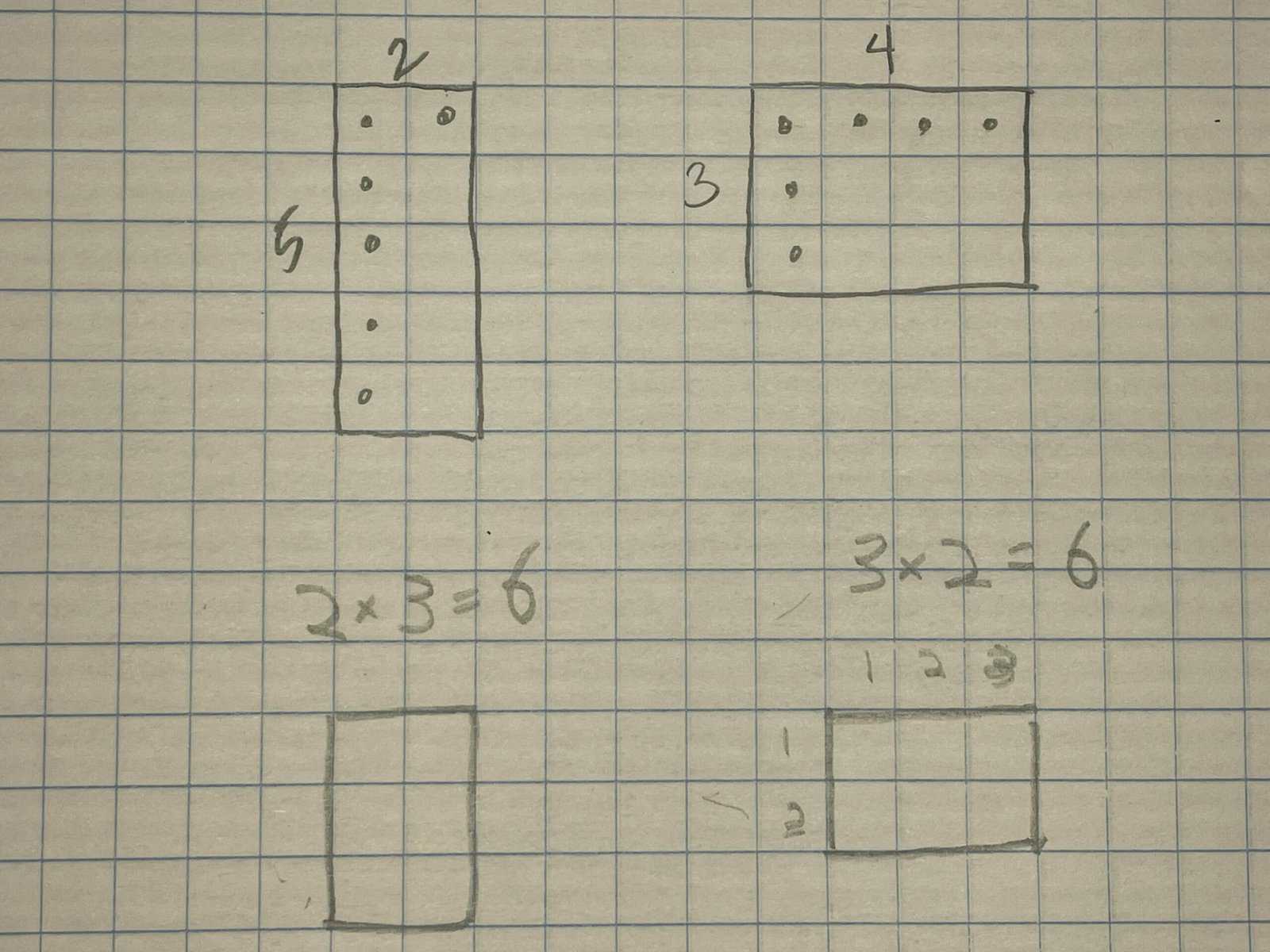

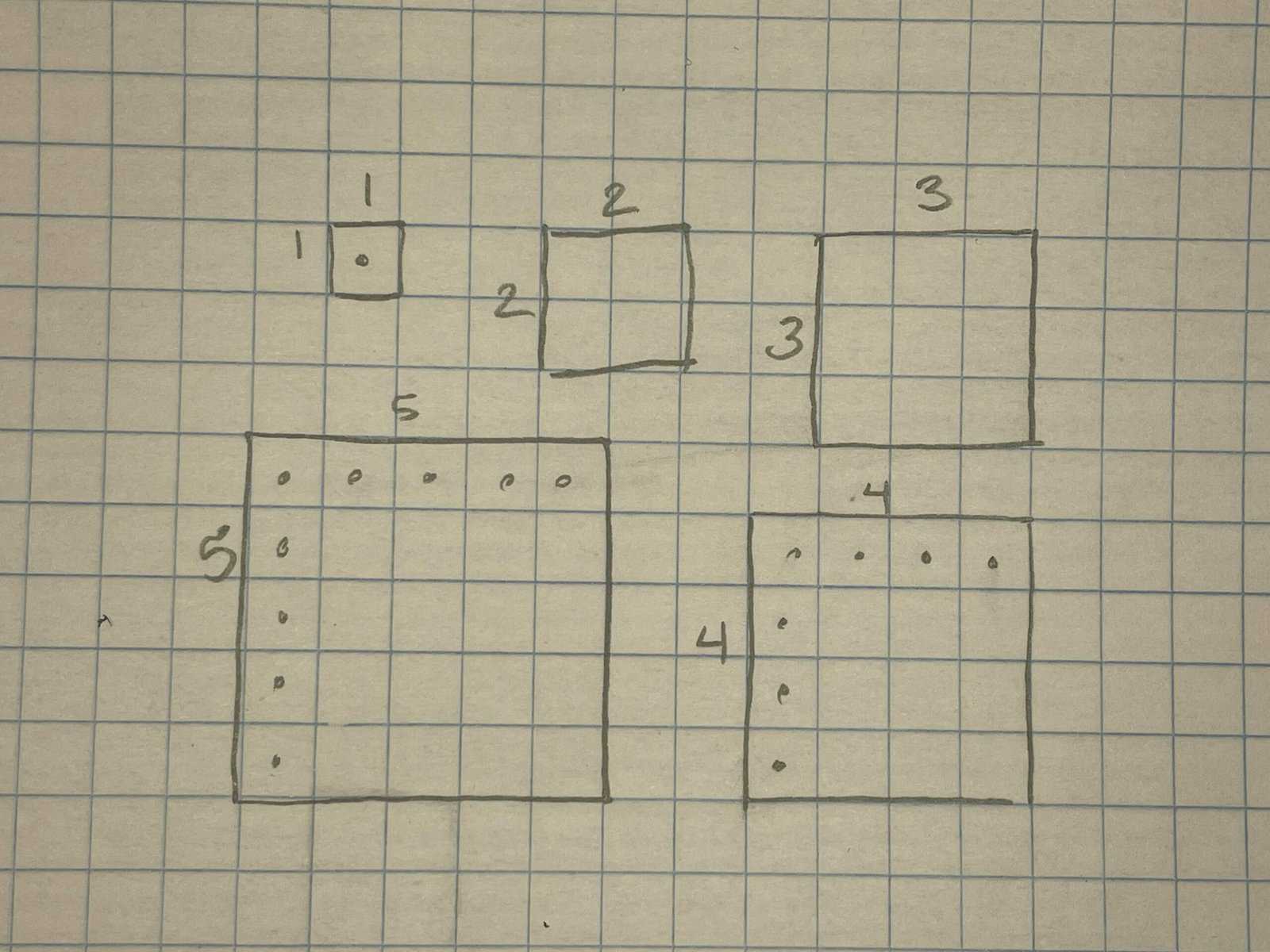

Using those same 1s through 5s facts, a piece of grid paper each, and our pencils, we learned to draw rectangles that were, for example, $3$ squares long by $2$ squares high, count the squares inside the rectangles ($6$ squares inside both of these), and associate them with the multiplication problems they represent.

After a couple rounds of practice and gentle corrections, the four of them together drew rectangles representing almost all of the multiplication facts we’d already discussed. This crew was quick to observe that the rectangles of related (paired) facts were just rotations of each other and so basically the same rectangles. A little more prodding got them to notice that the unpaired facts — those facts with matching factors — were unique and different from the other facts. These were the only facts that generated perfect squares!

(Note here on geometry: These squares led the students to doubt themselves at first. Like many students, they did not think of squares as a type of rectangle. Since I had asked them to draw rectangles, they thought it was wrong, believing that a square was not a rectangle. Just a note to watch out for opportunities to correct this frequent misunderstanding!)

These were, in fact, simple closed arrays. Two days later, their teacher informed me that they had been drawing these rectangles and counting the squares relentlessly since, and some of the students reported showing it to their families. They insisted we do more together, so we explored multiplication facts up through 10s.

Closed arrays of this type, where we draw rectangles whose dimensions match the factors in the multiplication problem, reappear later in the form of scaled drawings as well as a variety of other contexts.

In the immediate, closed arrays give students a way to begin to understand multiplication problems out of context, to strengthen counting skills (mostly in learning how to keep track), and to bridge counting to skip-counting to multiplication, and to create and explore. They are hands-on, artistic, and creative tools in the progression of symbolic thinking we ask of students. They give an anchor to understanding and remembering the definition of area as representing the number of square units (squares) that can cover the 2-dimensional surface. They give students a place to start discovering the ways math is all around them when they see patterns of floor or ceiling tiles, items lined up on shelves, and more.

However, I did find that, even with this quick-learning group, it took a few rounds of gentle, individual correction for them to accurately understand what I was talking about and how to draw them. In many of my other groups, even up through 6th grade, I have noticed that this step of individual understanding of the symbolic “closed” arrays is missing and undermining the students’ abilities to understand the later tools and models below. I recommend not underestimating this step of individual correction, as the understanding that comes from it is the basis of so much more to come.

Open Arrays: Abstraction (Generalizing Patterns), Place Value, and Two-Digit Multiplication

As certain curious students are inclined to do, one of my students in the group above decided to try a really big rectangle. I’m not sure the actual dimensions of his rectangle, as I didn’t count, but it took up well over half a standard piece of grid paper. He tediously counted over the 2 days in between my visits and proudly reported that the answer was $321$. When I asked him what the multiplication question was, he gave two numbers that were not quite right, but were relatively close to a product of $321$. I know that there was a miscount somewhere in his problem because his rectangle was not $3$ by $107$ (the two prime factors of $321$), but he was close enough that I believed he had the idea and we moved on.

This student’s experience previews what can easily go wrong when we try to use closed arrays to represent larger and larger multiplication problems:

- We may simply not have enough space on our paper to count that large a rectangle

- We can easily lose count or miscount either along the sides of the rectangle and/or within the area inside the rectangle

To help overcome these challenges, we further abstract the arrays and the multiplication problem. Open arrays look very much like the area model (in the next section). In fact, I’m not sure where along the continuum one becomes the other.

Open arrays…

- may or may not be to scale

- are a further abstraction and decontextualization from closed arrays

- often use a scaffolding tool such as bars and dots that hearken back to base10 blocks

- are most useful for double-digit multiplication

- require students to know some basic multiplication facts and have strategies for other facts

- require students to be able to decompose numbers as the sum of other numbers

- demonstrate visually the distributive property of multiplication

- give students an alternative interpretation of division other than “total split up into even groups”

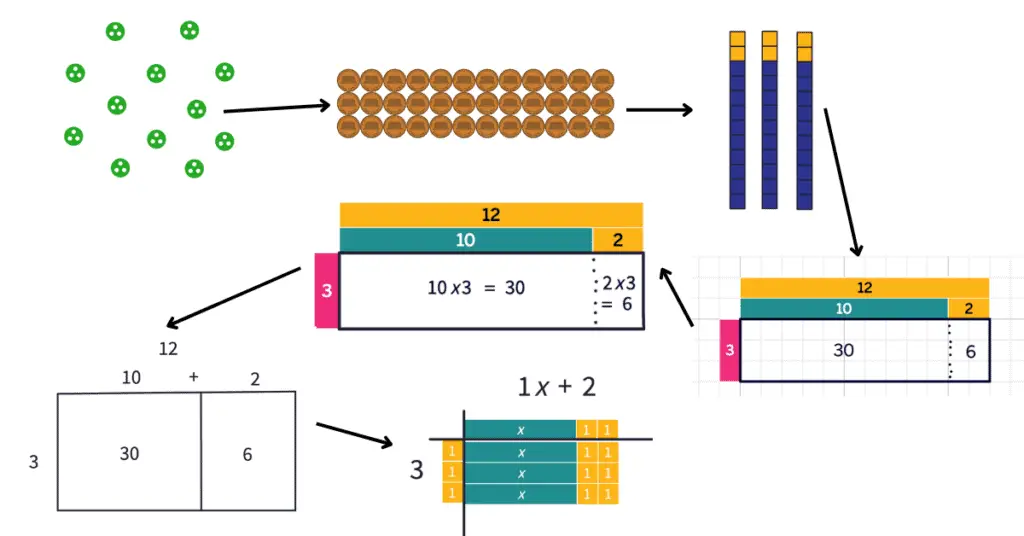

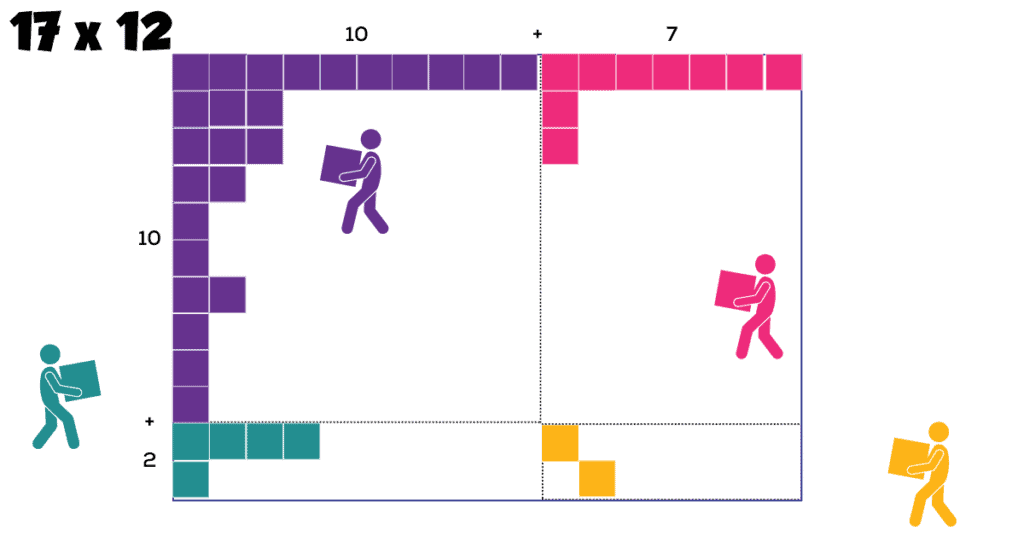

In an open array, at least one factor is decomposed into two or more addends (numbers added together to get the total). Ideally, these addends would be easier to multiply than the original number (because of having lots of zeros in the numbers and/or being basic, known multiplication facts). Most often, students are guided to decompose the factors into their expanded forms. This guidance reinforces the study of place value as well as being a standard way of making these easier-to-multiply decompositions.

Instead of actually using a scaled grid, each factor is written or represented (in its decomposed form) along the top of a rectangle (one factor) and along the side of the rectangle (the other factor), respectively. The idea is to then visualize the full rectangle as divided up into subdivisions guided by the decompositions along the top and side. Each subdivision covers an area computed by a simpler multiplication problem, and students can add all the areas together at the end of the problem.

There are a variety of ways to guide students through this transition from closed to open arrays.

- Physically represent the factors along the top and side with number tiles. Have the students draw the implied rectangle. Then have them fill it in using number tiles again to find the product.

- Represent the factors along the top and side with bars (10s) and dashes (1s). Move students through drawing and counting shapes (squares, bars, and dashes), then writing the numbers (100, 10, and 1 respectively) inside each shape, and finally into leaving off the shapes.

- Replace the bars and dashes along the top and side with whatever decomposition of the factors comes naturally to the students, have them multiply by parts and then sum the components. Point out when the parts of certain decompositions are easier to multiply than others, guiding them to use place value to simplify the arithmetic along the process.

Area Model: Multi-Digit Multiplication and Division, Polynomial Multiplication and Division

As mentioned above, it’s not actually clear to me what stage to shift the language from “open arrays” to “area model.” Thus, you might think of area model as a late-stage open array.

Area models…

- are not usually to scale

- are most useful for double- and triple-digit multiplication

- require students to know some basic multiplication facts and have strategies for other facts

- require students to be able to decompose numbers into their expanded form

- demonstrate visually the distributive property of multiplication

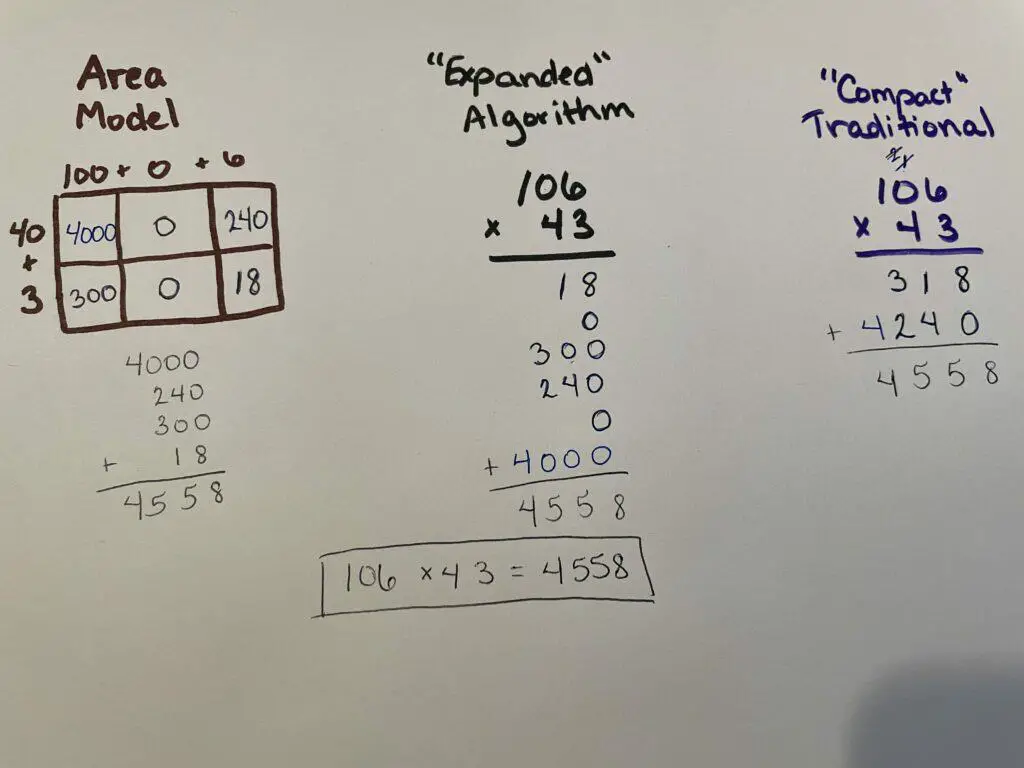

- show the exact same steps as other multi-digit multiplication algorithms, organized in a more visual way

- give students an alternative interpretation of division other than “total split up into even groups”

In arithmetic, area models generally show only the numbers outside and in (no bars and dashes, for example), the major implied rectangle, and often the subdivisions of the rectangle created by the factor decompositions. The factors are usually decomposed into their expanded forms, where each numeral is written as the number it represents in its place value with addition signs in between. The multiplication then follows as with any later-stage open array.

By decomposing each factor into its expanded form, we can see parallels between area model computations and other multiplication algorithms, even the standard algorithm. Turns out, the computations are all the same computations, just different ways of keeping track!

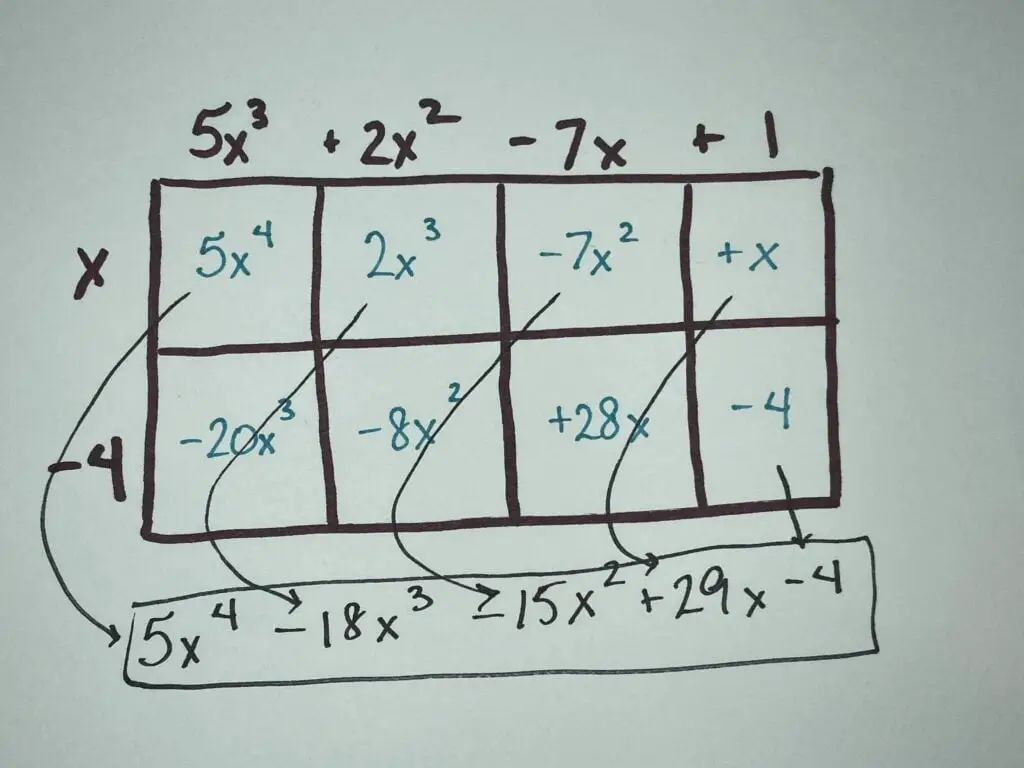

Another advantage of the area model is its extension into algebra and polynomial multiplication (as well as factoring). Because the analog of the traditional method gets very messy very quickly in algebra, students may find the area model in algebra useful well beyond 2- or 3-term expressions. Students do have to know how to multiply individual monomials (single terms) and either know or know how to generate the exponent rules. Using the area model can also help avoid certain really common mistakes and misconceptions.

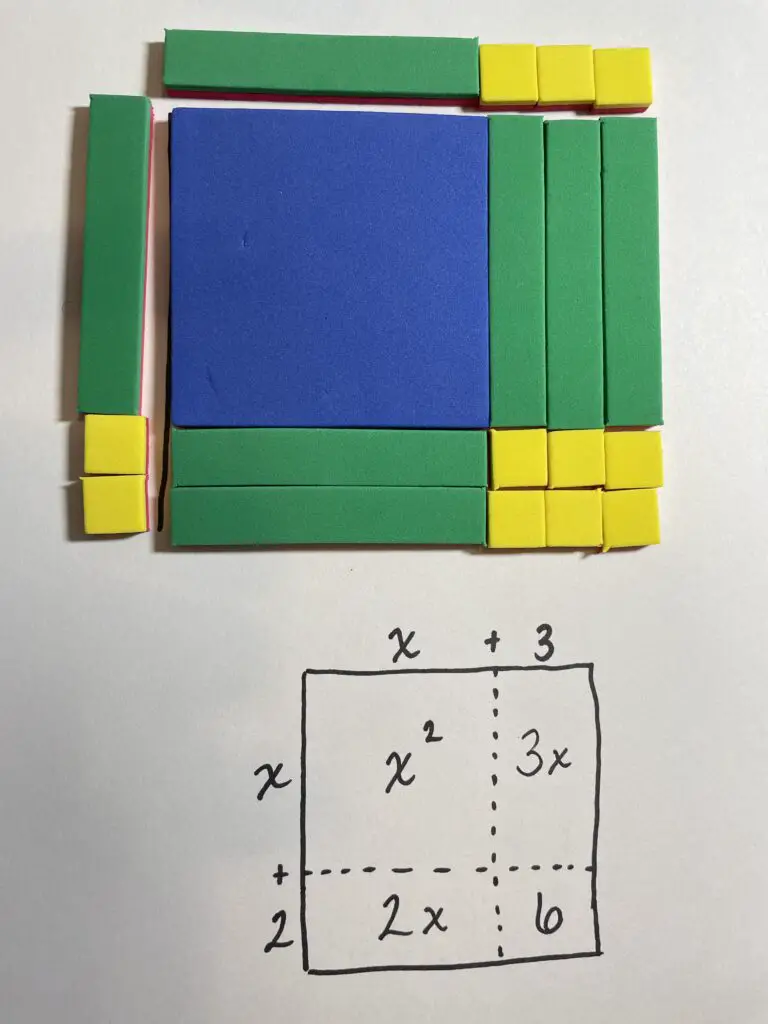

Algebra Tiles: Polynomial Concepts and Operations

Algebra tiles are to algebra as number tiles are to arithmetic. They have similar limitations as well as uses. Algebra tiles are manipulatable, physical representations of the area model in algebra.

They are limited to first- and second-degree polynomials. However, this is often enough to transition students from the physical manipulatives to more abstract representations that do adapt to higher-powered polynomials.